The ongoing push by Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose and state Rep. Brian Stewart, R-Pickaway, to make Ohio’s constitution more difficult to amend has stirred up controversy, and understandably so. Most Americans like democracy, so asking them to give some of it away is not an easy sell. LaRose initially claimed he was trying to protect Ohio’s constitution from “special interests” and “out-of-state activists.” But as Stewart seemed to acknowledge weeks later, the real goal is to protect the Ohio constitution from certain kinds of Ohioans, including the majority of Ohioans who would likely support a state constitutional right to abortion.

The clock ran out on the 134th General Assembly before Stewart could round up enough votes in the Ohio House to pass his plan, but he is now trying again with what one expert says is his worst version yet. House Democrats have gone to great lengths to try to stop this proposal, even working with dissident Republicans to elevate Rep. Jason Stephens, R-Lawrence, to the House speaker’s chair over the Republican caucus’s official nominee. Whether such efforts will succeed remains to be seen.

In this tug of war over Ohio’s constitution, it is worth noting that Ohio went down this road once before. For much of the 19th century, a supermajority requirement made the Ohio constitution very difficult to change.

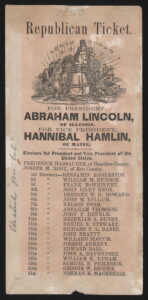

It didn’t go well. In fact, the supermajority requirement came to be so disliked that historian Charles B. Galbreath argued in his History of Ohio that the landmark 1912 Ohio constitutional convention might not have happened without it. (Galbreath, a Republican activist, was in an ideal position to understand this, having served as convention secretary.)

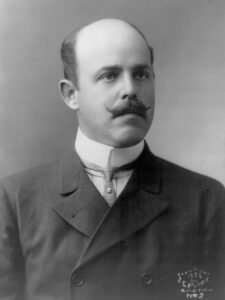

Figure 1. Historian Charles B. Galbreath served as secretary to the 1912 Ohio constitutional convention. (Image from the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

The 1912 constitutional convention was a key moment in Ohio history. It made Ohio democracy more accessible to the people by introducing the initiative and referendum and it made state government more responsive to the people through an array of other reforms. But some delegates said the single most important reform they could make would be to lower the threshold for voter approval of constitutional amendments to a simple majority. Ohio has used this standard ever since.

This is the standard LaRose and Stewart are trying to change—a standard Ohio House Democrats are trying to protect.

Ohio’s First Supermajority Standard

Ohio’s first supermajority standard for voter approval of constitutional amendments was not as straightforward as the 60 percent standard LaRose and Stewart are now pushing. For whatever reason, delegates to the 1850–51 Ohio constitutional convention decided that the constitution should only be amended if approved by “a majority of the electors voting at such election.”

This wording sounds innocuous, but it amounted to a tough supermajority requirement. Rather than simply having to earn a majority of those voting on a particular question, advocates for any change to the Ohio constitution had to earn yes votes from a majority of all ballots cast in the entire election. This was a high bar to clear. Then as now, Ohio voters sometimes skipped questions about the state constitution.

The 1857 election shows just how daunting this supermajority standard was. In that election, Ohio’s first Republican General Assembly proposed five amendments to the Ohio constitution. Figure 2, from Galbreath’s History of Ohio, summarizes the results.

On each of these questions, more Ohioans voted in favor than against. But each question still failed because the number of “yes” votes cast on the question fell well short of a majority of all votes cast in the 1857 election.

This supermajority requirement made the Ohio constitution so difficult to amend that, for more than 20 years, it was not amended at all. Proposals for change routinely failed even though majorities often supported them.

Over time, this became a problem. A major reason for calling the 1850–51 constitutional convention was to straighten out structural problems with Ohio’s judiciary. As the years passed, it became clear that, despite some changes, the structure of the judiciary under the 1851 constitution remained deeply flawed.

A major problem was the lack of a robust appellate court system. In the middle ground between the common pleas courts and the Ohio Supreme Court, the 1851 constitution had created a system of “district courts” consisting of panels of three common pleas judges and one Supreme Court justice. Because this tier of the judiciary lacked dedicated judges of its own, the district courts seem to have only created more work for the other tiers. For Supreme Court justices, it was a burden to crisscross the state to attend the district court panels. The panels also sometimes included common pleas judges hearing a case for a second time, a fact that may have made the district court panels reluctant to undo common pleas decisions. The system was a “total failure,” with the district courts only serving as “a half-way house to the Supreme Court,” as the Cincinnati Daily Gazette would later describe it.

By the 1870s, Ohio Supreme Court was falling badly behind on its caseload. In part to address this problem, Ohioans voted in 1871 to hold another constitutional convention. Delegates to the convention drafted an entirely new constitution in 1873 and 1874, one that included judicial reforms and an array of other changes. But in the end the proposed new constitution was soundly rejected by voters. (Disagreement exists as to why. One possibility is that the question became conflated with a separate controversy over temperance, a hot button social issue in that era.)

The Search for a Supermajority

For the court system, the situation was becoming desperate. The Supreme Court had fallen four years behind on its caseload, meaning that a case could take anywhere five to seven years to work its way through the judiciary. The glacial pace of Ohio’s courts caused “many persons to abandon their rights rather than ruin themselves by asserting them,” former Ohio Supreme Court Justice Rufus P. Ranney observed in 1875. The burden was “especially ruinous to the poor and to men of small means, who can neither stand such deprivation of their rights, nor the heavy expenses necessary to preserve them,” Ranney wrote.

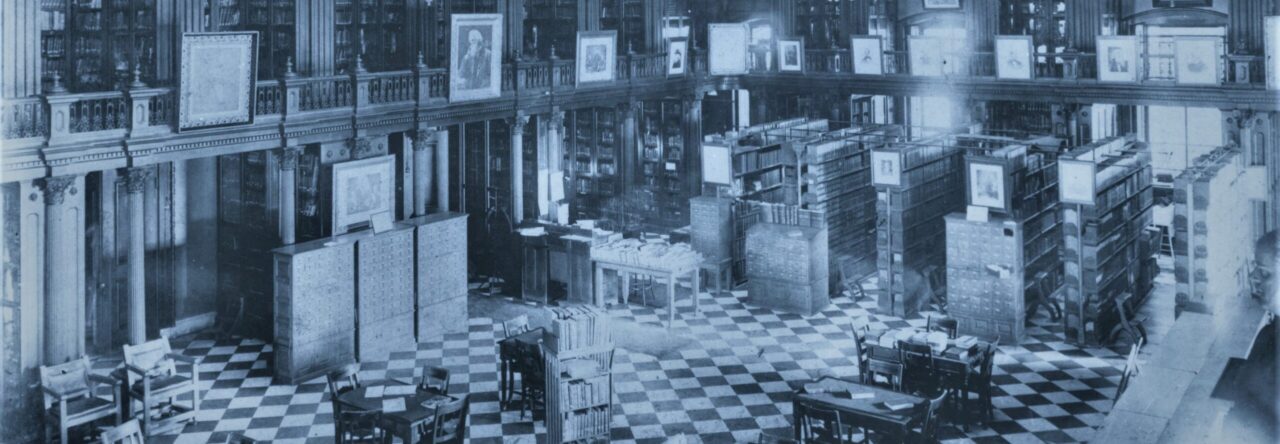

Figure 3. For decades, most voting in Ohio was done using pre-printed tickets distributed by party activists outside polling places.

In 1875, the 61st General Assembly proposed a constitutional amendment to allow a special commission to help the Ohio Supreme Court catch up on its caseload. But the challenge posed by Ohio’s supermajority standard was enormous. Of the 11 constitutional amendments proposed up to that point, all had failed, despite majority support in many cases. (Among them: an 1857 proposal to reform the district courts.)

Both of Ohio’s major political parties went all in on the question, urging their county party organizations to print ballots (or “tickets”) for distribution outside of polling places that only included one option on the proposed constitutional amendment: “For the Commission.” In previous elections, the parties might have left the decision on a question like this to voters. Not this time.

With preprinted party tickets only offering voters only one explicit choice on tickets, Ohioans finally met the tough supermajority standard. A commission began work in 1876 to help eliminate the Ohio Supreme Court’s caseload. The task took three years.

Success was temporary, however. The structural problems in Ohio’s judiciary had not been corrected, and work soon began to pile up again for the Ohio Supreme Court. In 1883, the amendment permitting Supreme Court commissions was again invoked, and a second commission began work on the new backlog.

Clearly, judicial reform was needed. The 65th General Assembly proposed a constitutional amendment that year to replace the district courts with a new system of circuit courts to include dedicated appellate judges. Once again, as in 1875, both political parties distributed tickets outside of polling places that only included one explicit option on the proposed constitutional amendment: For the amendment. By dragging voters along with preprinted tickets, Ohio’s political establishment got the amendment passed. The result was a more robust system of appellate courts for Ohio. (The new courts, known as circuit courts, were forerunners of Ohio’s modern courts of appeals system.)

It had become clear that, so long as they worked together, Ohio’s major political parties could drag voters along into delivering a supermajority for a constitutional amendment. But a new election law soon eliminated this option. In 1891, to reduce voter fraud, the Democratic 69th General Assembly eliminated use of party-printed tickets by implementing a new system of government-printed ballots known as the “Australian ballot.” Under the new system, all ballots would include an explicit “yes” or “no” option for constitutional amendments.

With political parties no longer able to pull voters toward “yes” on constitutional questions, three proposed amendments failed during the 1890s despite strong support from voters.

In 1902, the General Assembly came up with a workaround, passing Senate Bill 320, also known as the “Longworth Act.” The new law allowed political parties to formally endorse or oppose a constitutional amendment at their party convention, then register that position with the Ohio Secretary of State. Once the party’s position was on record, the vote of anyone choosing to cast a straight party ticket would automatically count toward the party’s position on the amendment.

Figure 4. A year after introducing the Australian ballot, the Ohio General Assembly added the option of straight party ticket voting. To vote a straight ticket, a voter marked a circle under their preferred party’s device (not shown). The Republican device was an eagle. The Democratic device was a rooster.

Figure 5. The Longworth Act was sponsored by state Sen. Nicholas Longworth, a Cincinnati Republican. Longworth later served as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

With parties again able to nudge voters toward support of a constitutional amendment, five different amendments were approved in 1903 and 1905, including one amendment that gave the Ohio governor a veto for the first time. Four of the successful amendments had been endorsed by both political parties. (The Ohio Democratic Party had not taken a position on the veto question.)

In 1908, the 77th General Assembly repealed relevant portions of the Longsworth Act, perhaps cooling to the idea of further constitutional change. Two years later, the 78th General Assembly did an about-face, inviting voters to approve a new constitutional convention. The legislature also passed Senate Bill 33, which allowed straight party ticket votes to count on the convention question. The constitutional convention was endorsed by both parties and approved overwhelmingly by voters.

The Legacy of 1912: A Constitution Closer to the People

The 1912 constitutional convention unleashed an immense amount of reform. In all, voters approved 34 amendments. One clarified that the Ohio General Assembly could protect workers’ health and safety, establish a minimum wage and regulate the length of the workday. Another enabled a modern system of universal workers compensation. Still other amendments created Ohio’s system of primary elections, permitted the progressive taxation of income, protected home rule by cities, and created the initiative and referendum.

Despite all this reform, some delegates felt the most important action they could take would be to make the constitution easier to amend. On April 23, 1912, a Committee on the Method of Amending the Constitution proposed replacing Ohio’s long standing supermajority standard with a new simple majority standard. As committee chairman Starbuck Smith of Cincinnati explained:

Every member was of the opinion that on this committee rested the greatest work that this Convention was called upon to do; to provide a simple and easy method of amending the constitution, because if we do that it matters not so much what else we do; the people will have the machinery whereby they can, in a simple and businesslike way, get what they want.

Starbuck Smith

Making the case for his proposed amendment on the convention floor, Smith noted that 30 out of 48 states were already using a simple majority standard, and that several states had moved away from tougher standards since 1851, when the Ohio constitution had been ratified by voters.

Delegates did not need a hard sell. They were bursting with ideas for constitutional reform, and they knew how difficult reform had been under the supermajority standard that applied during the previous six decades. Of the 26 constitutional amendments that had failed since 1851, 19 had received more “yes” votes than “no” votes, including multiple proposals for tax reform and to change the way state legislative districts were drawn.

Without dissent, the 1912 convention voted 102-0 to ask voters to approve a reworded Article XVI that included a new simple majority standard. As Delegate David Cunningham of Harrison County saw it:

Let us make it [the constitution] easy of amendment. That is my theory about it. It was a mistake in the framers of the constitution of 1851, that they made that constitution too difficult to amend, and we have had to resort to various devices to get it amended…. I think if the constitution with this proposal in it is adopted by the people in a very short time they will regard it as the dearest right they have, the ease with which they can amend their constitution.

David Cunningham

Voters ratified the amendment. Now, 110 years later, LaRose and Stewart are pushing to roll this right back.

LaRose and Stewart have dressed up their proposal to make Ohio’s constitution more difficult to change in lofty language, but some of their arguments seem thin. In his November news release for example, LaRose emphasized that nine states have a supermajority requirement of some kinds for citizen-initiated proposed amendments. But given that the legislature quickly broadened Stewart’s supermajority proposal to apply to all proposed amendments (including those proposed by the legislature), the more relevant point might be that most states trust simple majorities on constitutional amendments. (In 1912, Starbuck Smith counted 30 such states. There may be more today.)

The 1912 Ohio constitutional convention attracted national attention. Among those who took an interest was Theodore Roosevelt, who visited the Ohio Statehouse on Feb. 21, 1912, to address the convention.

Figure 6. Theodore Roosevelt visited Capitol Square on Feb. 21, 1912. In this photo, he is standing in front of the Neil House, across from the Ohio Statehouse. (Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

“I believe in pure democracy,” the former president told assembled delegates. “With Lincoln, I hold that ‘this country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it… Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it.'”

If LaRose and Stewart get their way, Ohioans will have a more difficult time exercising this right in state affairs. ♦

Sources

- Charles B. Galbreath, History of Ohio, Vol. II (American Historical Society, Inc., 1925), particularly chapters 6, 7, 9 and 10.

- Lee E. Skeel, “Constitutional History of Ohio Appellate Courts,” Cleveland Marshall Law Review 6, Issue 2 (1957), 323–330.

- Ohio Constitution – Law and History, a website maintained by Cleveland State University Professor Steven H. Steinglass. Of note is this list of past constitutional amendments proposed by the Ohio General Assembly.

- Kenneth C. Sears and Charles V. Laughlin, “A Study in Constitutional Rigidity,” Part II, University of Chicago Law Review 11 (1944), 389–406.

- F.R. Aumann, “The Development of the Judicial System of Ohio,” Ohio History Journal 41, No. 2 (April 1932), 195–236.

- “The Ohio Judiciary,” Cleveland Daily Herald, Jan. 11, 1875, 2.

- “Something more to be voted For,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, Sept. 16, 1875, 1.

- “For Commission,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, Oct. 12, 1875, 4.

- “Johnson and Niles Head the Ticket,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Aug. 27, 1903, 1–2.

- Laws of Ohio 88, 449 (Senate Bill 373, creating the Australian ballot); Laws of Ohio 89, 432 (Senate Bill 279, enabling straight ticket voting); Laws of Ohio 95, 352 (Senate Bill 320, the Longworth Act, allowing straight tickets to count on proposed constitutional amendments); Laws of Ohio 99, 120 (House Bill 1007, largely repealing the Longworth Act)

- Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Ohio, Vol. II (Columbus: F.J. Heer Printing Co., 1912) 1365–1366, 1371.

Figures

- Franklin County at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century (Historical Publishing Company, 1901), 461, via the Columbus Metropolitan Library’s Columbus in Historic Photographs collection.

- Charles B. Galbreath, History of Ohio, Vol. II (American Historical Society, Inc., 1925), 69.

- Library of Congress.

- Ohio Revised Statute §2966–32 as published in Clement Bates, The Annotated Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, Fourth Ed., Vol. I (Cincinnati: W.H. Anderson Co., 1903), 1678.

- Library of Congress via Wikipedia.

- Columbus Metropolitan Library’s Columbus in Historic Photographs collection.

Mike

Strong work

I.B.T.C.

This is incredibly well researched. A worthy addition to Ohio history!

Christine

John, thank you for your in depth history on Ohios’ constitution. It’s so frustrating how republicans twist things to get what they want. Recall HB6 that has become a massive scandal/political corruption. The wording they used , the scare tactics the Chinese want to take over the electric grid! That bill should have been doomed from the start. First energy wouldn’t even show us the ledgers to prove they were on the brink of bankruptcy. I will bookmark for future reference.